Tracy Ross

The Colorado Sun

While studying air quality during the ultra-fiery summer of 2020, two Colorado State University researchers discovered tree leaves ‘close their pores’ to keep from inhaling smoke

Wildfire smoke is terrible for humans, but it turns out it’s terrible for trees, too, according to two researchers at Colorado State University who found that when fires are blazing, some trees “shut their windows and doors and hold their breath.”

Delphine Farmer is a chemistry professor and Mj Riches is a postdoctoral researcher in environmental and atmospheric science at CSU. Together they study air quality and the ecological effects of wildfire smoke and other pollutants in CSU’s Chemistry department.

One morning in August 2020, they were at their field study site in the Manitou Experimental Forest near Woodland Park looking at the chemical emissions from ponderosa pine trees with the aim of understanding how they impact atmospheric chemistry, when smoke from multiple fires burning around the West “overwhelmed” them and created an opportunity.

Fall of 2020 was a bad season for wildfires in the western U.S. with the reported number of fires well above 10-year averages in Alaska (65%), the Rocky Mountain region (95%), the Great Basin (117%) and the Northern Rockies (121%). Surrounding regions had a fiery year, too, with Northwestern fires averaging 115% higher, Southern California fires 123% higher and Southwestern blazes 121% above average. And in Colorado, it was the year the Cameron Peak fire burned 208,913 acres, the East Troublesome fire burned 193,000 acres and the Pine Gulch fire burned 139,007 acres.

All of those fires created massive amounts of smoke, Farmer and Riches wrote for the reader-friendly academic news publisher The Conversation, so they had a lot of it to study at their research site.

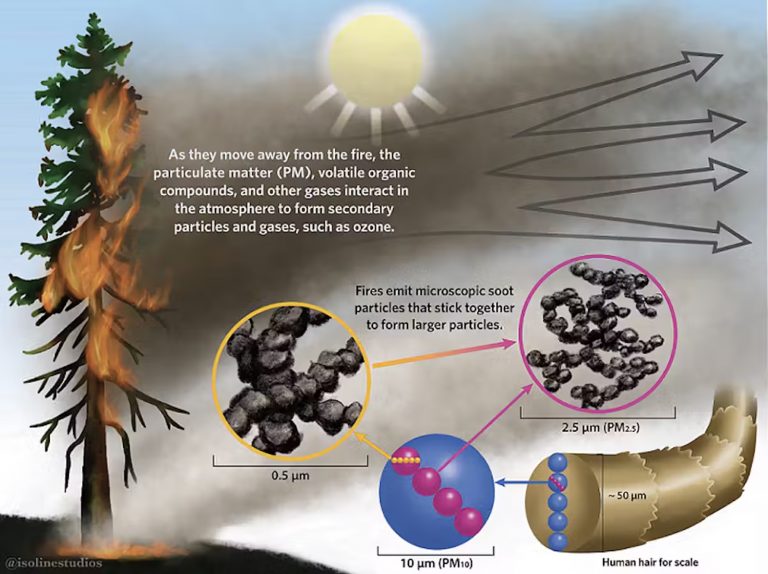

The study plants, which have pores on the surface of their leaves called stomata that “are much like our mouths,” they wrote, “except that while we inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide, plants inhale carbon dioxide and exhale oxygen.”

Both humans and plants inhale other chemicals in the air around them and exhale chemicals produced inside them — “think coffee breath for some people, pine scents for some trees,” Farmer and Riches said in their laypersons’ summary of formal research published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters in March 2024.

Unlike humans, however, leaves breathe in and out at the same time, constantly taking in and releasing atmospheric gases. But due to logistics and safety, scientists before Farmer and Riches didn’t understand how leaves reacted to fire, because wildfires are so hard to predict and it’s not the safest thing to be outside studying anything in smoky conditions.

The two wrote that they didn’t set out to study plant responses to wildfire smoke. “Instead, we were trying to understand how plants emit volatile organic compounds — the chemicals that make forests smell like a forest, but also impact air quality and can even change clouds,” they wrote.

On the first morning of heavy smoke, they did their “usual test to measure leaf-level photosynthesis of ponderosa pines,” they wrote, and were surprised to discover that the tree’s pores were completely closed and photosynthesis was nearly zero.

They also measured the leaves’ emissions of their usual volatile organic compounds and found very low readings, they said. And they discovered, “that the leaves weren’t ‘breathing’ — they weren’t inhaling the carbon dioxide they need to grow and weren’t exhaling the chemicals they usually release.”

Being scientists, they weren’t satisfied with their initial findings, so they pressed a little further, trying to “force photosynthesis to see if they could ‘defibrillate’ the leaf into its normal rhythm,” they wrote. “By changing the leaf’s temperature and humidity, we cleared the leaf’s ‘airways’ and saw a sudden improvement in photosynthesis and a burst of volatile organic compounds.”

What that told them was “some plants respond to heavy bouts of wildfire smoke by shutting down their exchange with outside air,” they wrote. “They are effectively holding their breath, but not before they have been exposed to the smoke.”

The “smoke-tree / forest work is all published” in peer-reviewed scientific journals, Farmer told The Colorado Sun, and she currently has a master’s student working in the CSU greenhouse to expose crop plants to smoke.

Although Farmer doesn’t think about trees in terms of having intelligence, she says they do have a useful strategy to minimize exposure to smoke.

“I think this research points to challenges that not just forests, but also crop systems, are facing with the emerging prevalence of wildfire smoke,” she said. “There is a clear need to better understand how plants will respond to this threat in our changing climate not just for the health of our forests, but also for our ability to grow food.”